Whether presidential or parliamentary, the system in Turkey can only function with an independent judiciary.

A historic window of opportunity is opening these days, allowing Turkey to become a state of an advanced democracy and the rule of law in a short time.

Reason: The People’s and Nation’s alliances, which propose a “Strengthened Parliamentary Presidency” and “Strengthened Parliamentary” systems, do not have the power to change the Constitution on their own but must reconcile.

If Turkey seizes this historic opportunity, it can quickly become a stable and advanced state of the law with a pluralist democratic order. Two years before the 100th anniversary of the Republic, it can stop the regression towards the multi-party unity of powers and autocracy of the pre-1960s.

But this once-in-a-century opportunity is about to slip away.

Because debates focused on who will form the government perpetuate the judiciary’s dependence on politics, neglecting that Turkey’s main problem is making the judiciary effective and efficient, compliant with the law at the highest level, accountable and fully independent.

Civil society needs to intervene and create demand and pressure on citizens for “stability in the state, not in power” to seize this historic opportunity…

A mentality that sacrifices the state for the stability of governments

Turkey’s governance problem is not the fragmentation of political movements and the inevitability of coalitions but the shallow mentality that coalitions are “bad” and should be avoided at all costs, which is incapable of deriving progressive methods from the diversity in representation… This shallow intellectual impasse resorts to simplistic and unsustainable artificial methods instead of finding sophisticated methods to ensure stability tailored to the realities of the country; it ignores the fact that the judiciary, which it sees as a stumbling block, is the assurance of stability in the state, and it is impossible to succeed without an independent judiciary, regardless of the system of government.

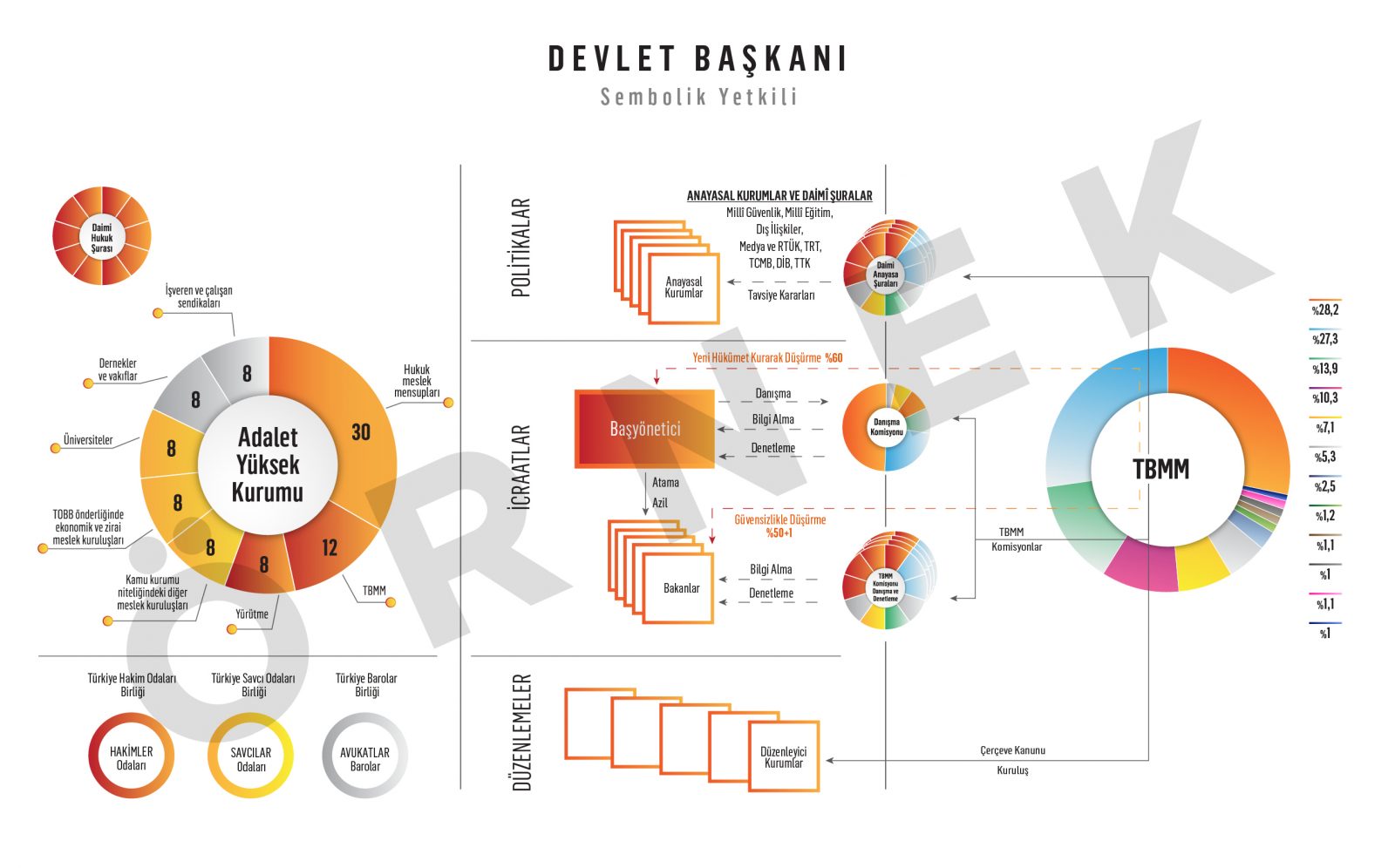

It sacrificed the fair representation of the people in parliament for the sake of stabilising the governments to save the country from the pre-1980 coalitions that collapsed one after another and dragged the country to the brink of bankruptcy. It created an artificial formula that gave a majority of 60% in parliament to the party that received 35% of the votes in the elections. To counterbalance the effects of this artificial majority, it shared the executive powers with the president.

By consolidating all executive powers in his hands, it has also led the president to dominate all state powers, the parliament and the judiciary. The judiciary, which already appeared to be an extension of the government, completely lost its power to balance the government and parliament. Thus, focusing only on bringing stability to the government has led to a loss of stability in state governance. Moreover, the people have learned through bitter experience that the lack of fair representation in the parliament leads to instability in state governance.

Judicial independence must come first

There are proposals in the public domain to reorganise the High Council of Judges (HSK) as the “High Council of the Judiciary”, to divide it into a “Council of Judges” and a “Council of Prosecutors”, to remove the Minister of Justice and his deputy from the Council, and to have its members elected by the Parliament.

These proposals listed under the main headings are far from achieving complete independence for the judiciary, ensuring that it provides quality services to society, complies with the law at the highest level, and is effectively accountable! On the contrary, they reinforce the political stranglehold on the judiciary.

The judiciary is the most critical power of the state. Because the judiciary ensures justice in state administration and society. Justice is a more important public service than security, economy, health, education and training.

To establish justice, it is first and foremost necessary to guarantee in the Constitution that the judiciary is fully independent, accountable and effective. Within this framework:

– All provisions relating to the judiciary, including professional judicial organisations, should be elaborately regulated in a separate chapter in the Constitution.

– The management of professional judicial organisations should be elected from among themselves by their members in office.

– The legislature and the executive should be prohibited from having any say or influence in the administration of the judiciary.

– The judiciary should prepare its budget autonomously.

– High quorums in enacting laws concerning the judiciary, review by the Constitutional Court before their entry into force, or retroactive effect of annulment decisions should be envisaged.

Electoral thresholds concern judicial independence

The electoral threshold is proposed to be reduced to 7% or 3%.

Some public opinion polls show that there are two parties above the 20% threshold, four parties between 20% and 5% and six parties below 5% but above 1%. When the election threshold is 10%, approximately 25% of the society will not be represented in parliament. If the threshold is lowered to 7%, this rate may drop to around 20%; if it is 3%, it may drop to nearly 10%.

Introducing safeguards in the Constitution is not sufficient to maintain judicial independence. When the parliamentary arithmetic is artificially altered, it is possible to overcome the heavy quorums stipulated in the Constitution and to take advantage of the weaknesses in the Constitutional protection system to pass laws that undermine judicial independence. The most influential force to guarantee judicial independence is the common sense of society. Common sense emerges in society when different political views and interest groups reach a consensus. Social common sense and common mind dominate the laws enacted by the parliament, representing different political views through reconciliation. For the parliament to make prudent decisions, it is necessary to achieve fair representation of different views not only in the parliament but also within political parties. Therefore, fair representation of the people in parliament is required not only for a stable executive but also to ensure the independence of the judiciary.

The parliamentary arithmetic is healthy in that it necessitates the formation of coalitions to make decisions such as passing laws and approving and overthrowing the government. On the other hand, it enables the formation of different coalitions on different issues instead of ossified coalitions. Such a parliamentary arithmetic brings stability to the state and reconciliation to society. This will require developing a rational and easy-to-operate governance formula that allows for the reconciliation of different political views. The first and most important prerequisite for such a formula is a fully independent judiciary that effectively protects the Constitution. Other key building blocks are to ensure that as many different views as possible are represented in parliament and that the country is not left without a government.

The fragmented parliamentary arithmetic allows for a large number of coalition possibilities. In fact, according to the latest opinion polls, the parliament, if formed, would allow for more than ten coalitions, including one party from the 1st or the 2nd party.

To ensure stability, it is crucial not to maintain unchanged governments but to avoid being without a government and to build confidence that governments will be governed under the law and in a predictable manner. When the judiciary is fully accountable, independent and effective, and when it is easier to form a government and harder to overthrow it, the “fear of being without a government” disappears and “rule-based, predictable” governance is achieved.

Therefore, for a stable, rule-based, predictable and law-abiding administration:

– Electoral thresholds can be reduced to 1%.

– Electoral districts should be organised to minimise residual votes and ensure the representation of different parliamentary views.

– Restrictions on intra-party democracy should be lifted; all delegate systems and block lists in elections, which are contrary to the principle of democratic governance, should be banned.

– In all elections, including candidate primaries, elections for single positions should be held in two rounds and elections for multi-person positions should be held in one round in a proportional procedure under judicial supervision.

The executive must be institutionalised, and its administration must be democratised

The People’s Alliance says that the president and his deputies should be elected, the ministers should become MPs, and they should be dismissed with a vote of no confidence. The 6-Party Commission agreed that the authority to form a government, i.e. the prime ministership, should be given to the first three parties in turn, that it should receive a simple majority (50%+1) vote of confidence, and that it should be overthrown by a qualified majority (e.g. 60%), provided that a preliminary protocol is signed.

When the ruling powers, which use the state’s enormous power and therefore can dominate other powers, become overpowered, the balance and harmony between the already weak powers is disrupted. The ruling power, which also dominates the parliament, also makes the judiciary dependent. Therefore, excessive empowerment of the ruling power poses a threat to the independence of the judiciary.

The fact that the parliament can overthrow the government by forming different coalitions may prevent the government from becoming overpowered to a certain extent. However, more than this measure may be required in the face of enormous executive capabilities. Yet, effective ruling powers in the parliament may render this measure meaningless. A more effective measure would be to improve the institutional structure of the executive and distribute its authority in a balanced manner. The main functions of the executive, such as policy-making, execution and administrative regulation, should be decentralised among institutions. Our country is situated in a sensitive geography, in the midst of different power blocs and various cultural movements. A strong institutionalised executive can provide more stable state governance by preventing wavering on crucial policy issues.

Therefore, measures should be taken to improve the institutional structure of the executive power to make it inclusive of different views, to ensure team management and democratisation of the administration, and to make it balanced and harmonious within itself and with other powers. For this purpose:

– Constitutional institutions representing the overwhelming majority of the society can be founded and empowered to set policy on key issues such as national security, foreign relations, national education, media – Radio and Television Supreme Council, Turkish Radio and Television Corporation, CBRT, etc.

– Permanent councils could be established to coordinate with the constitutional institutions and formulate recommendations with the participation of all stakeholders.

– Approval and dismissal of ministers appointed by the chief executive could be subject to different criteria. The first government formed by the elected or appointed chief executive could be approved by a simple quorum, while its dismissal could be subject to a qualified higher quorum of 60%.

– Ministers could be approved or dismissed by the parliament with a simple quorum of 50%+1 or directly dismissed by the chief executive.

– Official platforms could be established where the chief executive could meet with the heads of political parties or groups, and ministries could meet with their parliamentary committees to exchange information, oversee and consult. MPs could effectively collaborate with the executive for legislative activities through these platforms.

Dismissal by forming a new government instead of affirmative no-confidence

Focusing on who will elect the person to form the government makes it difficult to find a stable solution. It may be easier and more beneficial for the country to find a formula where the elected person can be replaced before the end of their term, if necessary, rather than focusing on who selects and appoints this person. Institutionalised and accountable governance will ensure stability and predictability. Stability in governance can be achieved even if administrators change. Stability in state administration can be achieved not by not replacing the administrators but by not making arbitrary changes and by replacing them quickly and effectively when necessary, without creating an administrative gap.

The 6-Party Commission proposes to make the parliament’s dismissal of the government conditional on the pre-designation of the new prime minister. The “affirmative no-confidence” proposal suggests an almost impossible method, requiring political parties to agree on who the new prime minister will be and stick to it while simultaneously bringing down the current prime minister.

Inspired by small Northern European countries with high levels of education, prosperity and a culture of social reconciliation, this proposal is not in line with Turkey’s social fabric, political culture and habits. In those countries, the society resolves fundamental governance issues such as forming and dismissing governments in a high level of reconciliation culture and by consensus before coming to the parliament. This culture does not yet exist in Turkey. Moreover, even if this proposal could be implemented, it does not guarantee the formation of a new government that would receive a vote of confidence from parliament concurrently with the dismissal of the government. Since the approval of the prime minister does not necessarily mean the approval of the ministers, it is not easy to immediately form a new government to replace the one dismissed. It is virtually impossible to take the two decisions – to dismiss a prime minister and to approve a new one – in a single session of parliament.

This proposal rests on the assumption that existing alliances will remain intact. It prevents the formation of unions and social reconciliations between different views. If implemented, albeit challenging, it will lead to “lame duck” governments that have not received a vote of confidence.

However, the underlying objective of this proposal can be accomplished in a much simpler way. With the new government to be formed receiving a vote of confidence, the current government would automatically be deemed to have been dismissed, and the current government could be dismissed easily and simply. In this case, the country would not be left without a government or ministers, not even for a moment.

Everyone should participate in this debate and contribute to a permanent solution.